How one Colorado school is tackling pandemic gaps

It’s the third week of school at Remington Elementary in Colorado Springs and the first-grade teachers gathered in a small classroom say more students than usual are struggling with letter names and sounds — skills typically mastered in kindergarten.

A bar chart projected on a television screen bears out these observations, showing that 40% of the school’s first-graders are behind in literacy, with most of those scoring in the lowest “red” category and the rest in the second-lowest “yellow” category on a common reading assessment.

“Yeah, that’s scary,” said Principal Lisa Fillo, who’s led a reading instruction overhaul at the school over the past several years.

Now, educators at Remington, like those across Colorado and the nation, are beginning to size up the challenge ahead, particularly in the early grades where the building blocks of successful reading are formed. The pandemic torpedoed many of the school’s recent literacy gains and threw an especially disruptive wrench into the education of Remington’s 105 first-graders, whose pre-K year was cut short and whose kindergarten year was marked by flip-flops between online and in-person learning.

“Kindergarten was broken up so much,” said Fillo. Last year, “they had like … three first days of school.”

To be sure, Remington’s youngest students are struggling with more than just reading. They’re out of practice with classroom routines like following instructions, rotating through learning stations, or even getting out a sheet of paper. There’s an undercurrent of anxiety about catching COVID or dying from the virus among some families. And to complicate matters further, the school has already seen an uptick in student absences, which means some children are missing out yet again.

While Remington teachers will no doubt spend the coming months helping kids regain both social-emotional and academic ground, reading instruction comes with a particular sense of urgency here. The school made big gains after its reading revamp: Scores on third-grade literacy tests shot up and the share of early elementary students who were seriously behind went down.

Plus, Remington’s staff know that if early gaps aren’t addressed they tend to grow with each passing year.

“The older they get, the harder that is, and the more [students] feel it because they’re so self aware,” said Courtney Bruce, a first-grade teacher who taught third grade at a different school last year.

Fillo said weak reading skills can have life-long repercussions.

She recalled asking a prison guard she met on a plane, “What’s the percentage of your inmates that can’t read?”

The man responded, “Oh, like 99%.”

More than three-quarters of adults in prison have weak reading skills, according to a 2003 study of literacy rates from the U.S. Department of Education.

Locking in the basics

As part of Remington’s reading makeover, which began about five years ago, the school adopted a “structured literacy” approach that involves directly teaching students reading skills in a systematic way. The school uses a well-regarded reading curriculum — Core Knowledge Language Arts — and devotes a hefty chunk of the school day to literacy — two hours and five minutes. Starting this week, some children will also spend two hours a week in after-school tutoring funded with federal dollars intended to help students from low-income families.

About 36% of students at Remington qualify for free and reduced-price meals, a bit higher than average in the 24,000-student District 49 and a little lower than the statewide average of 40%.

On a recent morning, it was easy to see the brisk pace of literacy lessons in Remington’s first-grade classrooms. Little time was squandered, with teachers offering pops of encouragement during lessons — and sometimes firm reminders: “Boys and girls, I should not hear any talking.”

In Bruce’s classroom, students arrayed on a rug around her chair gauged whether pairs of words had the same beginning sound. She whisked through the verbal exercise — “dime and penny,” “ring and red,” “king and kite” — listening for a sing-song chorus of “yeses” or “nos” after each set of words.

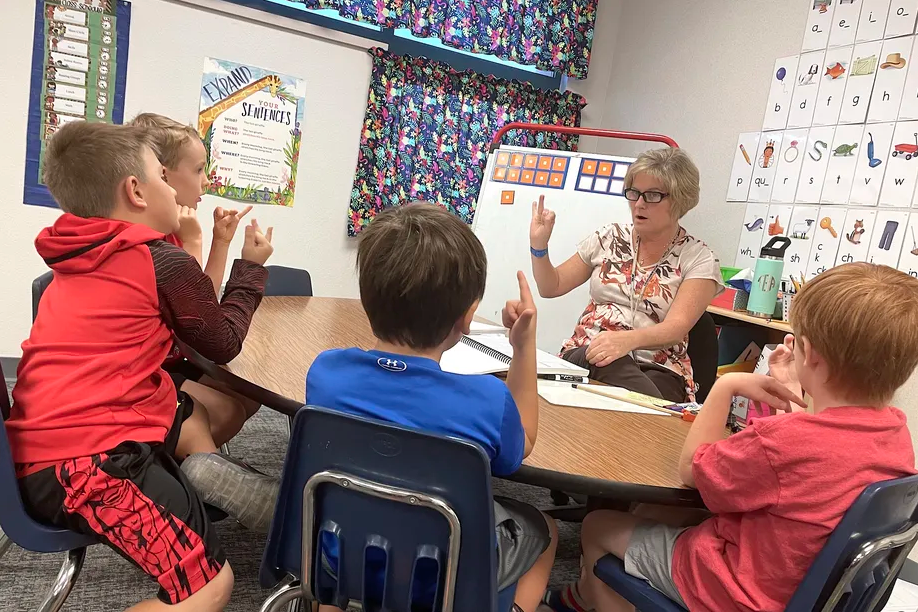

Down the hall, Trisha Butler guided four boys in spelling simple three-letter words on white boards at the back of her classroom. For the word “kid,” one boy paused, looking blank as the others started shaping the first letter with dry erase markers. Butler quickly noticed his confusion and reminded him how to form the letter k.

A minute later, there was another stumble when she asked the boys to replace the ending sound in “kit” with an “n” sound. The new word should have been “kin,” but one student chose an “m” instead of an “n,” so Butler quickly recapped the difference between the two letter sounds.

“This one is an ‘mmm’ sound, like monkey,” she said, pointing to the m. “I want you to have an ‘nnn’ sound like nest.”

While such lessons are not unusual in the early weeks of first grade, Remington’s educators say many students need more repetition this year to lock in fundamentals.

Yuki Rockwell, the school’s literacy coach, said Remington’s kindergartners learned letter sounds last year to some extent, but never got the consistency they needed because of all the disruption.

“It’s just not automatic coming into first grade,” he said.

Data quest

One of the constants in Remington’s approach to reading instruction is data — lots of it.

It’s on computer screens, color-coded wall displays, and woven through casual conversation. During a weekly first-grade meeting, teacher Jodi Price mentioned a struggling reader she and Rockwell worked with during summer school who needed 150 repetitions over three days to learn the “m” sound. It’s just one of hundreds of data points that help Remington educators figure out where students are and what they need to progress.

Rockwell maintains a display of red and yellow bookmark-like slips representing Remington students in every grade who’ve been assigned to intervention groups because of reading struggles. In first grade, there are 39 such students — most represented by red slips because they are far behind — plus two others that Rockwell is monitoring for possible reading troubles.

Rockwell’s goal is to ensure every first-grader has a solid handle on their sounds and letters by the end of the first quarter, and can confidently blend letters into full words by December.

“I think it’s very possible to close the gap,” he said. “We’ve just got to have very specific goals of what we’re shooting for.”

But he also knows that while teachers may foster impressive gains this year, some students won’t master every grade-level reading skill.

“The reality is we might … not be able to catch them up in a single year,” he said. “I know everyone wants to.”

As the recent first-grade team meeting wound down, Principal Fillo turned her attention from the bar charts on the TV screen to Rockwell, her reading intervention teacher, and her five first grade teachers — all sitting at small desks around the room.

Part cheerleader and part task-master, she weighed in on the formidable job ahead.

“If anybody can do it, it’s this team right here,” she said.

This article was originally posted on How one Colorado school is tackling pandemic gaps