Will politics eventually end the Olympics?

“Only the strongest shoulders can carry the hopes of a nation.”

– Katie Taylor, Irish gold medalist

The Olympic Games originated in ancient Greece in 776 BC and were performed every four years in honor of the god Zeus in Olympia on Peloponnese peninsula. The festival was a time for worship and unity. As a testimony to their serenity, all wars ceased during the games. This celebration was held faithfully until the birth of Christianity. When nations became divided over politics and religion and no could longer compete in unity, Roman emperor Theodosius I put an end to them in 394 AD.

In the late 18th century, French nobleman Pierre de Coubertin had a vision to revive the Olympics to develop the minds and the bodies of French youth by exposing them to other cultures. In 1892, he planted the seeds for our modern Olympic games at a meeting of the Union des Sports in Paris. Delegates from Belgium, England, France, Greece, Italy, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and the United States unanimously supported his vision of nations competing with each other in sport and in unity.

Thirteen countries competed at the Athens Games in 1896. By 1924, a Winter Olympics was also added to the Games. The first winter Games were held at Chamonix, France, in honor of Pierre de Coubertin. But the Summer Games remain the focal point of today’s modern Olympics competition.

“The Olympics bring out your passion for your country more than anything else.”

– Clara Hughes

Like the political and religious conflicts that eroded the true intent of the Games, politics during the 20th century tainted the Olympics. Germany used professional athletics to propagandize Nazism in the 1936 Berlin Games. At that time, only amateurs competed and the Nazis openly disrespected the strict rules of the Games. This disregard for the intent of the Games has continued ever since.

Since WWII, Pierre de Coubertin’s dream of creating an event for nations to express national pride by competing on the world stage has been abused for political and personal gain. Athletes that used to compete for love of country have given way to professionals who use the Games as a personal and a political forum.

“I said I was ‘The Greatest,’ I never said I was the smartest!”

– Muhammad Ali

Egypt, Iraq and Lebanon boycotted the Melbourne Games in 1956 to protest seizure of the Suez Canal. And The Netherlands, Switzerland and Spain joined them protesting the USSR’s invasion of Hungary. In Mexico City in 1968, two U.S. Black runners used the Olympic podium to protest racism. In 1972, Palestinian terrorists massacred Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympic Games.

Following the tragedy at the 1972 Munich Games, there was no violence at the Montreal Olympics in 1976. But again, the Games became a political exhibition hall when 33 African nations and over 500 athletes boycotted the Olympic Games as a protest against South Africa’s apartheid policies.

In 1980, Jimmy Carter pressured the U.S. Olympic Committee to boycott the Olympics in Moscow to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Japan, West Germany, China and others followed. This embarrassed the Soviets in front of the world and these were the least followed games ever.

By 1983, relations between the U.S. and the USSR deteriorated to the point that the Soviet Olympic Committee said they feared for the lives of their athletes at the 1984 Los Angeles Games. They led a boycott of the Games by the Eastern-bloc. Participating nations ridiculed them and claimed they were sore losers and this was childish political pay-back for the U.S. led boycott of the 1980 Soviet Games.

“Anyone who doesn’t regret the passing of the Soviet Union has no heart.”

– Vladimir Putin)

The 1996 Atlanta, Georgia, Olympics involved a political tragedy, when a nail-laden pipe bomb killed a mother of a young girl. Over 100 people were injured and a Turkish cameraman perished. Numerous radical political groups claimed credit for this terrorist attack but none were prosecuted.

For once, competition trumped politics during the 2000 Games in Sydney, Australia. The statement of unity and peace made by North and South Korea when they marched together under one flag during the opening ceremonies was a rare occasion that reflected the real intent of the Olympics.

The only other expression of true comradery and sportsmanship was from 1956 to 1964 when East and West Germany unified as a single team. But after 1964, their gesture of good faith soured with a nasty political dispute between the East and West over who displayed the awards and medals.

“The only flag that shall unite the East and West is one flown by the Soviets.”

– Nikita Khrushchev

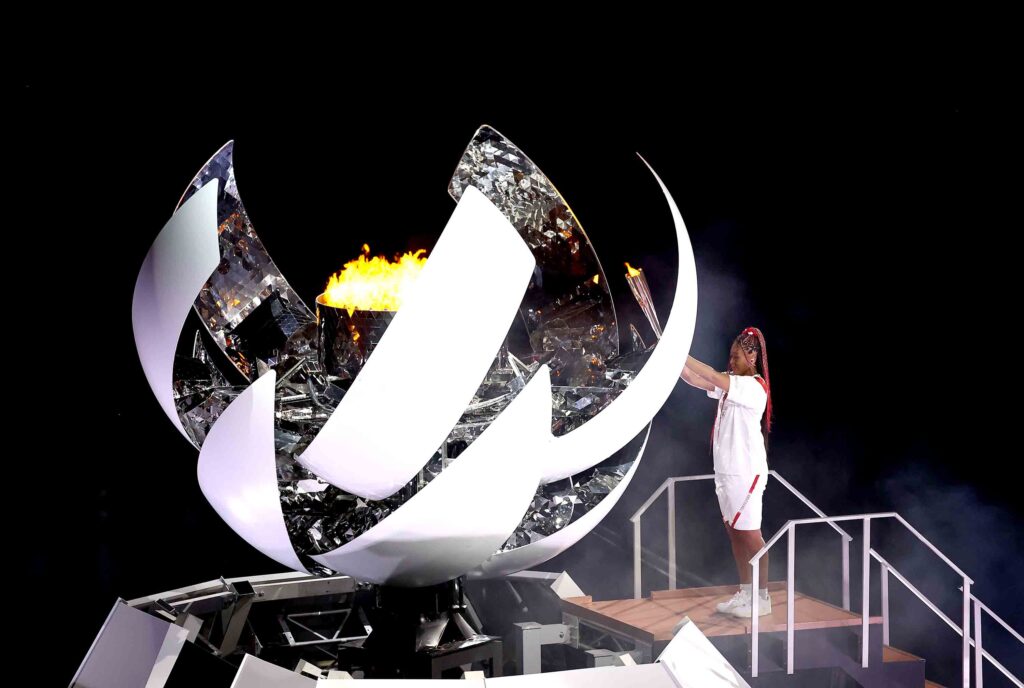

Responding to rumors that disgruntled athletes planned to use the 2020 Tokyo Olympic rostrum as a soapbox to express their grievances, International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach retorted: “The Olympic Games are not about politics. They are about sports and competition only.”

He cited Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, which bans any form of political protest during the Games. The IOC Athletes’ Commission expressly stated in guidelines released in January: “Politics” included gestures like kneeling and raising fists, and displaying political messaging like signs or armbands. He said athletes can express their views to the press, or social media but not on the Olympic field.

At the 2020 Tokyo Games, five female soccer teams took a knee ahead of their matches. Great Britain and Chile took a knee and the United States and Sweden did the same. New Zealand took a knee before their match with Australia, but the Aussies remained standing proudly arm in arm.

Gold Medalist Jesse Owens said, “Politics and the Olympics don’t mix.” The Greeks organized the Olympics as a sanctuary for all nations to gather and compete in contests in unified peace. It was a time for athletes to dual for awards, not for soldiers to fight wars. It was not a time to promote one’s personal political agenda. These were the specific rules set down by the Greeks, much as our rules today.

“If you don’t go to the Olympics to win for your country, then don’t go at all.”

– Jessie Owens

When the Greeks created the Olympics, they were candidly aware that inviting nations to lay down arms and compete in sports would not create peace. Sports and politics have nothing in common. The Greeks were not trying to influence decisions on politics, war or peace. But they did know that every nation would welcome a few days of competitive sport as a break from fighting each other.

Attending the Olympic Games is an honor that unites the world. Everyone respects the same rules, without prejudice for gender, race or politics. When the Games mutated into political and religious sparring, Theodosius I ended them. That can happen again if we continue to allow politics to disrupt this time for competitive unity.

“The unifying power of the Games can only unfold if everyone shows respect for and solidarity to one another. Otherwise, the Games will descend into a marketplace of demonstrations of all kinds, dividing and not uniting the world.”

– IOC President, Thomas Bach

This article was originally posted on Will politics eventually end the Olympics?